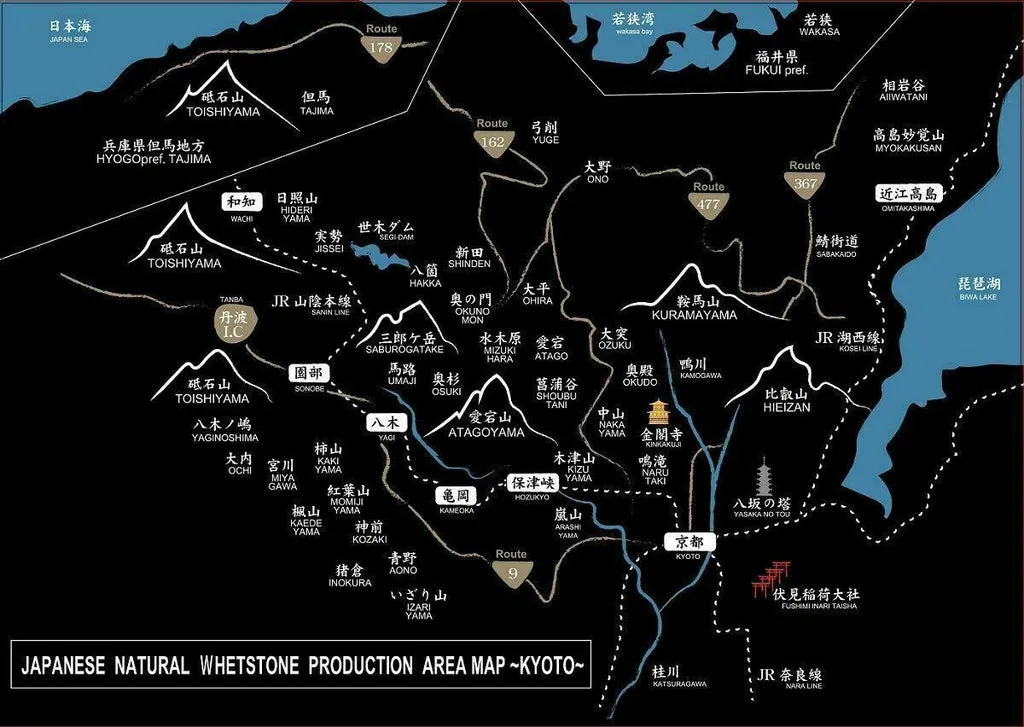

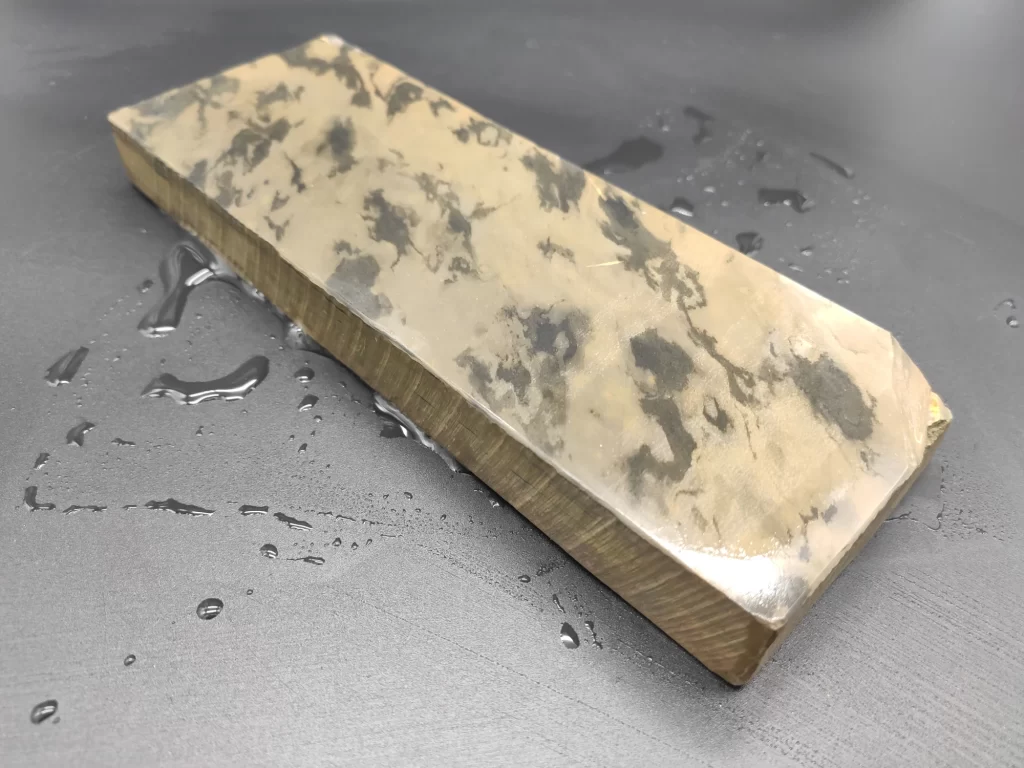

Japanese natural sharpening whetstones, also known as toishi (砥石), are not only tools, but also a cultural heritage, valued worldwide for their unique grinding properties and aesthetics. These stones, extracted from the mines around Kyoto, are divided into eastern (Higashi Mono, 東モン) and western (Nishi Mono, 西モン) groups according to their geographical position around Mount Atagoyama. Each mine has a distinctive history, stone texture, colour and abrasiveness, allowing for different finishes, from subtle Kasumi to mirror polishing. Collectors and craftsmen value these stones not only for their functionality, but also for their rarity, as most of the mines have now closed. This article gives a detailed description of each mine, based on Japanese literature and the notes of the old masters.

Eastern mines (Higashi Mono)

Aiiwatani / Aiwadani (相岩谷産)

The Aiiwatani Mine, often referred to as Aiwadani, is one of the most famous eastern mines, located near Kyoto, on the eastern side of Mount Atagoyama. Its stones have been mined since the Edo period (17th to 19th centuries). The Aiiwatani stones, in particular Asagi and Another one variations, characterised by a soft, uniform texture and a yellowish-green colour, which the craftsmen call "as calm as a spring sky" (『春の空の如く穏やか』, quoted from the notes of a 19th-century sharpening master). These stones are more suitable for sharpening knives and other tools than razors, giving a cloudy surface. Due to their limited quantity, Aiiwatani stones are highly valued by collectors and often fetch several thousand yen per kilo at auction.

Aiiwatani, also known as Aiwadani, is one of Kyoto Prefecture's old mines, located in the eastern part of the Higashiyama mountain range. The mine is famous for its pale greenish stones, which the artisans call "calm as the spring sky" (『春の空の如く穏やか), and its grey stones, which are often of medium hardness and fine grain. Stones from Aiiwatani are often used to sharpen kitchen knives as they give a subtle Kasumi finish. Due to their mild abrasive effect, these stones are favoured by both beginners and experienced craftsmen. Although the mine is no longer active, its stones are still valued by collectors and professionals.

Gosenryou (五千両)

The Gosenryou mine, near Kyoto, was known for its high quality natural sharpening stones. This mine supplied stones with a medium to high level of hardness and a fine grain size. Gosenryou stones are often used for sharpening knives and razors, as they provide a smooth and uniform finishing surface. Gosenryou 'Asagi' type stones are particularly appreciated for their ability to give a subtle Kasumi effect. Although the mine is no longer active, its stones are still highly valued by professionals and collectors.

Kinugasayama (衣笠山)

Kinugasayama was one of the old mines of eastern Kyoto, located at the foot of the Higashiyama hill, close to the centre of Kyoto. The site was historically known for its medium-soft natural sharpening stones, which were particularly valued for their versatile use as kitchen knives, shaving razors and various traditional carpentry tools. Although the mine never achieved the global recognition of Nakayama or Ohira, it was highly valued by local craftsmen for its balanced stone character.

The name "Kinugasayama" itself can be translated as "Silk Umbrella Mountain", and the terrain of the place actually resembles a light, rolling hill. The stones of the mine were mostly light yellowish, light greenish or greyish in colour, sometimes with subtle nashiji (pear peel) texture flecks. They were considered to be of medium hardness, which made it easy to obtain an even surface finish without damaging the edge of the blade when working on them.

By honing the Kinugasayama stone, it is possible to achieve a clean kasumi finishing on laminated blades, subtly highlighting the contrast between soft and hard steel. The abrasive structure of these stones also prevented the blades from "snagging" and gently removed material, making them ideal for both the initial sharpening and the intermediate stages before final polishing.

The Kinugasayama mine, like many other smaller mines in the Kyoto region, closed in the mid-20th century, but the surviving stones are now valued for the delicacy of their workmanship and their historical value. These stones are not very common on the collectors' market, but those who know the reputation of the area are keen to acquire them as well-balanced all-purpose sharpening stones with an authentic trace of old Kyoto craftsmanship.

Kizuyama (木津山)

Kizuyama was one of the lesser-known but reliable natural sharpening stone mines in East Kyoto. It was geographically located close to other famous mines such as Nakayama or Okudo, and therefore shared part of the same geological strata, but the stones extracted had a distinct character. Historical sources mention that Kizuyama was in operation until the mid-20th century and that its stones were mostly exported for local use and were placed in the hands of craftsmen in small batches.

Kizuyama stones were renowned for their relatively high hardness, but their distinctive feature was their soft grinding sensation. This meant that even at higher hardness, the stone did not 'stick' to the blade, but allowed the work to be carried out smoothly, which made it a favourite of professional knife makers and razor makers. They were used both for intermediate sharpening and for the final stage of sharpening and surface finishing.

The colour of the stones ranged from light greyish to a soft greenish, sometimes with subtle suji (vein) lines or nashiji spots. Due to their dense structure, Kizuyama stones prevented the blades from penetrating too deeply, making them safe even for very finely polished razor blades.

Kizuyama stones are rare today, as the mine has long been closed and its output was quite limited. Among collectors, these stones are considered a niche but very valuable find, especially for their sense of work and the clean sharpness of the result. Craftsmen who own these stones tend to keep them in their personal collections or use them for sensitive, handmade tools and knives, where a very gentle abrasive effect and precise control of the finish are required.

Nakayama (中山)

The Nakayama mine is considered the "queen" of Japanese sharpening stones because of its unrivalled quality. It operated from the 17th to the end of the 20th century on the eastern side of Atagoyama. Nakayama stones, in particular Another one and Asagi variants, are extremely fine-grained, allowing a mirror polish that is described as "clear as lake water" (『湖の水の如く清らか』, Toishi Shū notes). They are ideal for razors, katana swords and high-end kitchen knives. The mine is closed and Nakayama stones are among the most expensive on the collectors' market, sometimes costing tens of thousands of yen for a small piece.

Maruka from the Kato mine is particularly prized. This mine was closed in the middle of the last century due to the high risk of collapse.

Narutaki (Mukoda/Mukaida) (鳴瀧 or 鳴滝)

In ancient texts (Toishi Den, 『砥石伝』) Narutaki stones are said to be "soft as falling water". Narutaki is one of Kyoto's oldest and most historically significant natural sharpening stone mines, and its name is closely linked to the Japanese stone tradition. It was located in the eastern part of Kyoto, close to the Narutaki district of the same name, famous for its waterfalls and ancient temple gardens. The area has been valued since Edo for its special quality of honing stones, and its geological composition distinguished it from other surrounding mines.

Narutaki stones are renowned for their fine, highly uniform abrasive structure, which allows for a very high level of sharpening results. Due to their density and delicate, soft feel, these stones have been particularly valued by shaver makers, but are also suitable for finishing knives and other blades where a fine kasumi (fog effect) surface. The colour range was generally from light grey to yellowish, often with subtle suji by veins or nashiji type of texture.

Narutaki also distinguished himself with his variants, among which the following were particularly appreciated Asagi (light greyish-green) and Another one (slightly yellowish) stones with a particularly clean grinding feel and a light scum (slurry) by dissolution. Such stones allowed craftsmen to control the level of surface finish with great precision and to give the blade the perfect balance of softness and sharpness.

The mine was active until the first half of the 20th century when, like most of the old Kyoto mines, it ceased operations due to resource depletion and changes in market demand. Although Narutaki stones still occasionally appear in antique or collectors' markets today, they are very limited in quantity and extremely high in value. Because of its reputation and quality, the Narutaki name is often mentioned in classical sharpening manuals and in old masters' notes as one of the most prestigious mines in the Kyoto region.

Okudo (奥殿)

Okudo is one of the most legendary and highly regarded natural sharpening stone mines in eastern Kyoto. It was located in the Higashiyama Hills, in the same geological belt as Nakayama and Ozuku, but was distinguished by the quality and diversity of its strata. Although Okudo stones were often considered to be extremely hard, slightly softer variants were also found in this mine, which, thanks to their balanced abrasive properties, were particularly suitable for both razors and high-end kitchen knives.

Okudo stones were renowned for their extremely dense, homogeneous structure and remarkably clean surface. They were often yellowish-brown, greenish or greyish, often with subtle suji by veins or karasu (wing of a raven) drawings. Some of the most appreciated were Asagi, Another one and Karasu variations, each with its own texture and abrasive properties. Karasu from the Okud mine are particularly valued for their dark colour and their ability to give the blade a rich mirror finish, with no obvious streaks or abrasive marks.

Okud stones were known for their ability to create highly controlled suspensionwhich allowed craftsmen to precisely control the grinding process. For this reason, they were a particular favourite of razor manufacturers and knife sharpening professionals. As the hardness of the stones was often above average, they were particularly suitable for those who wanted a mirror-like surface without scratches or visible abrasive traces.

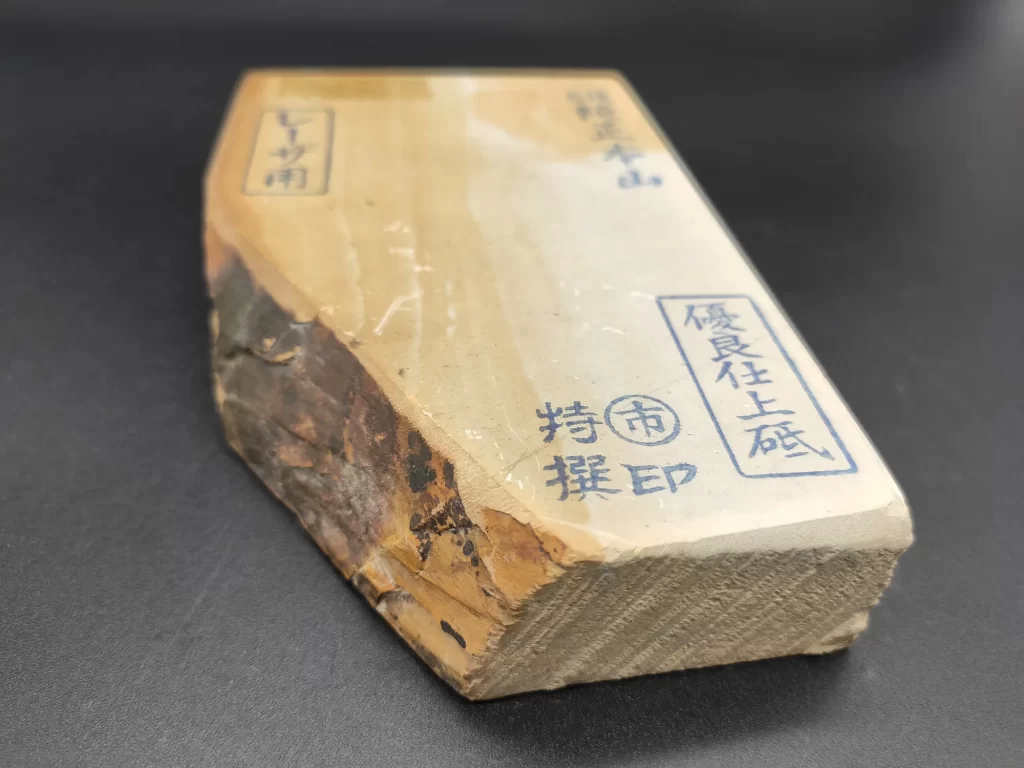

The mine operated until the mid-20th century, but eventually ceased operations due to limited deposits and costly exploitation. Today, original Okudo stones are extremely rare and precious among collectors and professional craftsmen, and are often considered among the finest natural Japanese sharpening stones in history. Many old masters referred to them in classical inscriptions as an example of the highest quality, and vintage stones bearing the Okudo name fetch extremely high prices at auction or in antique shops.

Okusugi / Oku sugi (奥杉)

Okusugi mine, named after the cedars (sugi), and was active until the end of the 19th century. Its stones, often Asagi type, light green, with a fine-grained texture, ideal for precision sharpening. Toishi Kō Okusugi stones are said to "give the blade a softness like cedar leaves". They are used for razors and small tools to Kasumi finishes. Due to their limited availability, Okusugi stones are rare and prized by collectors.

Ozaki/Osaki (尾崎)

Ozaki (sometimes spelled Osaki, Japanese: 尾崎) is one of the old and delicate mines of eastern Kyoto, where the stones are valued for their smoothness, medium hardness and a very soft, pleasant grinding feel.

The Ozaki mine is located on the eastern side of Kyoto Prefecture, close to other famous mines in the Higashiyama Mountains, such as Nakayama and Okudo.

Ozaki was one of the long-established mines, but it ceased operations at the end of the 20th century. Its stones have long been used both by professional sharpeners and in blacksmiths' workshops.

The stones are of medium hardness - they were usually classified as 中硬 (chu-ko) or 硬 (ko). Fine abrasive particles that allow gentle removal of the metal layer. A very uniform and smooth surface, often without large natural inclusions or cracks. Common colours: light grey, yellowish or slightly greenish tones. Occasionally, variations of the Asagi (浅葱) shade are found.

Used for the final finishing grind of kitchen knives to achieve a very sharp but subtle Kasumi (霞) effect.For sharpening razor blades to maintain a very sharp but softly "pulling" blade feel. Also for use on woodworking tool blades and chisels where a precise and clean edge was required.

As Ozaki stones are rarely found anymore and their quality is very high, they have a high value in the collectors' and craftsmen's market. Large stones with large dimensions, no inclusions and an evenly grained structure are particularly valued.

Some old craftsmen mentioned that Ozaki stones polished the iron very evenly and cleanly without removing too much metal, which is why they were favoured by blacksmiths before the polishing stage. Traditional craftsmen's notebooks (e.g. 砥石之本」 - Toishi no Hon) often recommend this type of medium-hardness stone for the final sharpening of knives.

Ozuku (大突)

Ozuku is one of the most famous and sought-after mines for natural sharpening stones, which operated on the eastern side of Kyoto Prefecture, in the Higashiyama mountain range. Although the mine officially closed in the second half of the 20th century, its name has remained synonymous with the finest and hardest natural Japanese stones of the highest quality, especially prized by enthusiasts of the traditional razor and the skilled sharpening of kitchen knives.

Ozuku stones are characterised by an extremely fine abrasive structure, often referred to as ultra-high-grade jiro-toishi. Toishi Hon Ozuku stones are said to "reflect the moonlight in the blade". They are usually very hard, but their uniform grain structure allows for an extremely clean, mirror-like blade surface. This characteristic made them a particular favourite of master razor makers who were looking for the maximum sharpness without sacrificing the cleanliness and integrity of the metal surface. Even masters of kitchen knife sharpening often chose Ozuku for the final stage, when an extremely smooth and sharp edge was required, especially for knives intended for fish or delicate work.

Ozuku stones can vary in colour from greyish, greenish to yellowish tones, but the most appreciated are those that are even in colour, without any distinct inclusions or cracks. Particularly rare and precious are Karasu Type Ozuku, with a darker, bluish-black pattern reminiscent of crow feathers. Such stones are considered by collectors to be the ultimate example of craftsmanship and aesthetics created by nature.

Historically, Ozuku stones were quarried in small mines, and the best layers were usually only accessible deep within the mountain. Old craftsmen and traders often reserved the best pieces for regular customers or gifts for important guests. Although the supply of original Ozuku stones on the market today is very limited, their name still remains the benchmark of quality among natural Japanese sharpening stones, and any authentic surviving specimens fetch high prices at auctions and in private transactions.

In addition to their practical qualities, Ozuku stones are also valued as aesthetic objects, thanks to their subtle colours, natural patterns and historical heritage. In collectors' circles, they are often considered not only as tools, but also as part of the heritage, testifying to the continuity of Kyoto's old sharpening traditions and the meticulous work of its craftsmen.

Sannodan / San no dan (三の段)

Sannodan, also known as San no Dan, was one of the limited but highly regarded mines in eastern Kyoto, geologically part of the Okudo region. In fact, it was one of the Okudo deposits or seams, which got its name from its location in the mine - the 'third seam' or 'third level'. The stones quarried from this site had very specific characteristics and were regarded as one of the finest forms of natural abrasive.

Sannodan stones were known to be very hard, but to maintain a delicate grinding action and to be able to form a very uniform slurry. This made them particularly desirable for shaving razor enthusiasts and craftsmen who wanted to achieve an ideal, clean, shiny surface without visible abrasive marks. Most of these stones were pale yellowish, greyish or greenish, some with subtle suji veins or nashiji texture. Although they were not as hard as Ozuku stones, their seamless structure and control made them one of the optimal options for high quality finishes.

One of Sannodan's most striking features is its ability to balance rapid grinding with minimal surface damage, so that knives or razors have a very clean, smooth edge after working with this stone. The stones from this mine were particularly suited Kasumi for decoration, where subtle highlights were needed hagane and jigane contrast without leaving abrasive traces.

The mine was active until the mid-20th century, but due to limited resources and costly exploitation, it ceased to operate. Nowadays, original Sannodan stones are a great rarity and highly valued by collectors and traditional craftsmen. They were cited by the old craftsmen as an example of finesse and craftsmanship, and in the historical notebooks of the masters San no Dan name often appears alongside names such as Nakayama or Okudo.

Shiroto (白砥)

The Shiroto mine, associated with Ozuku, was mined until the mid-20th century. Its stones, as the name suggests (shiro - white), are bright and soft, and suitable for final polishing. Toishi Den describes them as "pure as the stone of the temple". Shirot stones are used for razors and fine knives to achieve a mirror effect. The mine is closed and its stones are moderately rare.

Shoubudani (菖蒲谷)

Shoubudani is an old and highly respected mine of natural Japanese sharpening stones, located on the eastern side of Kyoto, in the Higashiyama Hills region. Historical sources mention Shoubudani as far back as the Edo period as one of the most reliable and high-quality suppliers of stones to the craftsmen of Kyoto, especially those who worked with knives, razors and Japanese calligraphy blades. Although the mine itself is now long closed, its name remains one of the most prestigious in the history of Japanese stones.

Shoubudani stones were renowned for their extremely fine abrasive structure and medium hardness. This made them ideal for both fine finish grinding (honing), both Kasumi for creating a type of surface where the blade has a subtle matt glow with a barely visible texture transition. These stones worked particularly well for knives and razors with softer steel blades or which required a slightly softer sharpening without breaking the grain or compromising the integrity of the edge.

In terms of colour, Shoubudani stones were usually light grey, yellowish, greenish or brownish, and particularly prized specimens had small, barely discernible mineral specks or fine natural bands. Some stones had Asagi shades of bluish-greyish tones, which were particularly appreciated by master shavers. Occasionally there were also Karasu darker versions, with delicate patterns resembling crow feathers, although these were rare and very expensive.

Historically, Shoubudani stones were exported not only to other regions of Japan, but also to China and Korea, where they were used for sharpening both metalworking and calligraphy tools. In collectors' circles, original Shoubudani stones are nowadays considered to be a valuable find, especially if they are preserved with old marks or stamps of the craftsmen. Due to the closure of the mine in the mid-20th century, authentic specimens rarely appear on the market and their prices are constantly rising.

This mine is considered to be one of those whose stones had a special grinding sensation - they worked gently but efficiently, leaving a smooth, clean blade edge. This was particularly important for traditional knife makers in the Kyoto region, who needed to achieve not only sharpness but also aesthetic surface integrity. These qualities are why Shoubudani stones are still remembered today as one of the most versatile and highly valued natural sharpening stones in Japan.

Takashima (高島)

The Takashima mine was located in the eastern part of Kyoto Prefecture, close to other well-known natural sharpening stone mines such as Nakayama and Shoubudani. Historically, the area belonged to the hills of the north-eastern region of Kyoto, which were known for their rich and varied abrasive rock strata. Takashima stones were mined as early as the Edo period, and in the 19th century they became sought after by both local craftsmen and blacksmiths and knife makers in other regions of Japan.

Takashima stones were renowned for their medium-soft texture, making them very popular with beginners and experienced craftsmen alike. This balance of abrasiveness made these stones particularly suitable for intermediate and final sharpening of knives, when it was necessary to form a uniform edge and prepare the blade for final polishing. Takashima stones often had yellowish, yellowish-grey or brownish hues, and some specimens showed subtle natural layer lines or mineral flecks, which were considered a sign of quality.

The main value of Takashima stones lay in their abrasive feel - they worked evenly and gently, creating a uniform, matt surface that could then be polished to Kasumi or even semi-mirror effect. For this reason, Takashima stones have often been used for both kitchen knives and traditional Japanese razors. They were valued by craftsmen for their ability to gently remove fine unevenness while maintaining a smooth and aesthetic blade profile.

The Takashima mine was officially closed in the mid-20th century, when many of the Kyoto region's natural stone sources began to follow or were shut down for safety and environmental reasons. Although most of the stones were mined before the Second World War, individual stones remain in the hands of collectors and professional craftsmen to this day. Authentic Takashima stones, especially those still bearing old makers' marks or remnants of the original label, are considered to be extremely valuable and their prices have been steadily increasing in recent years. It is one of those mines whose name is still associated today with the classic, elegant feel of Japanese cutting.

Takayama (高山)

The Takayama Mine, located in the eastern part of Kyoto, was active until the mid-20th century. Its stones, often Another one type, yellowish and fine-grained, suitable for final polishing. Masters describe them as "warm as sunlight" (『日の光』). Takayama stones are used for razors and knives for a mirror effect. The mine is closed and its stones are highly prized.

Takitani (滝谷)

The Takitani mine, named after the valley of the waterfalls, was mined until the late 19th century. Its stones, often Asagi type, greenish and hard, suitable for intermediate sharpening. Toishi Hon Takitani stones are said to "refresh the blade like water from a waterfall". They are used in katana swords and tools to Kasumi finishes. The mine is closed and its stones are rare.

Tukiwa / Tsukiwa (月輪)

The Tukiwa mine, located near Narutaki, was active until the early 20th century. Its stones are often soft and suitable for final polishing. The craftsmen call them "shining like the moon" (『月の輪』). Tukiwa stones are used for razors and fine knives to achieve a mirror-like surface. The mine is closed and its stones are moderately rare.

Yazutsu / Yadzutsu (矢筒)

The Yazutsu Mine, named after the valley in the shape of an arrow case, was mined until the late 19th century. Its stones, often Karasu type, dark and hard, suitable for intermediate sharpening. Toishi Den describes them as "tough as a soldier's armour". Yazutsu stones are used in katana swords and tools to Kasumi finishes. The mine is closed and its stones are rare.

Western mines (Nishi Mono)

Aono (青野)

The Aono Mine was one of the rarer but highly regarded mines in the western Kyoto region, located on the western side of Mount Atagoyama, an area traditionally known as Nishi Mon or West Side Mines. Although the Aono mine was never as large or as widely exploited as Ohira or Nakayama, its stones have long had a reputation among razor makers and knife sharpening enthusiasts.

The main characteristic of Aon stones is their light blue or bluish-grey hue, which gives them their name (Ao means blue, from - field or location). The stones were usually quite hard, but at the same time retained a subtle sense of grinding, which allows control over the removal of material and the creation of a very smooth, homogeneous blade surface. These characteristics made Aon stones particularly suitable for the final sharpening of razors and extremely hard tools, where not only sharpness but also minimal material removal was required to avoid resharpening the blade.

Unlike some other mines, Aono was not renowned for its wide variety of stones - most of the stones produced were fairly uniform in hardness and texture, which gave the craftsmen the opportunity to create a consistent, predictable sharpening process. This uniformity made Aon stones a favourite in the workshops of the old shaving knife makers, where consistent and controlled edge shaping was an essential requirement.

The Aon Mine ceased operations in the mid-20th century, but the stones that were excavated before then are considered quite rare and valuable today. Among collectors and professional craftsmen, authentic Aon stones are often associated with the razor culture of the old days, and their delicate grinding feel and light blue hue have become a real classic Nishi Mon the symbolism of the stones.

Ashiya (Ashidani/Ashitani) (芦谷)

The Ashiya mine in the Tanba region was mined until the end of the 19th century. Its stones are often soft and suitable for sharpening knives. Toishi Kō Ashiya stones are said to "add finesse to the blade". They are used in kitchen knives to Kasumi finishes. The mine is closed and its stones are rare.

Atagoyama

The Atagoyama Mine, located on Mount Atagoyama, was active until the mid-20th century. Its stones, often Asagi are grey, greenish and sufficiently fine-grained to be suitable for the final sharpening of knives, often with very large dimensions of 5 cm. and more. Masters call them "holy as the spirit of the mountain" (『山の神』). Atagoyama stones are used for razors and knives to achieve a semi-mirror effect. The mine is closed and its stones are highly prized.

Hakka (八箇 or ハッカ)

The Hakka mine, located in the western part of Kyoto, was mined until the late 19th century. Its stones, often Karasu type, dark and hard, suitable for intermediate sharpening. Toishi Hon Hakka stones are said to "give the blade its strength". They are used in katana swords and tools to Kasumi finishes.

The Hakka (八箇 or ハッカ) Sharpening Stone Mine is one of Japan's less documented sources of natural sharpening stones (JNATS), located in Kyoto Prefecture, probably near the Nakayama region, which is renowned for its high-quality sharpening stones. Hakka stones are said to be fine-grained, hard and suitable for the final stage of sharpening, especially for Japanese knives and razors, giving a polished, mirror-like surface to the blade, similar to Nakayama or Ohira stones. Their texture and composition, probably composed of fine silica particles, allow them to achieve an extremely high level of sharpness, but due to the limited scale of mining and the depletion of resources, these stones are extremely rare and valued by sharpening enthusiasts. Like many other traditional mines in Japan, the Hakka mine was probably closed after the Second World War, when synthetic sharpening stones and power tools reduced the demand for natural stones and depleted the mine's resources.

Hideriyama (日照山)

The Hideriyama mine, located to the north of the western mines, was active until the early 20th century. The Hideriyama (日照山) sharpening stone mine is one of Japan's sources of natural sharpening stones (JNATS), located in Kyoto Prefecture, close to other famous mines such as Nakayama or Ohira, and is known for its soft, medium-fine stones suitable for sharpening knives, razors and other tools.

In Japanese language sources, including specialist sharpening stone dealer websites and enthusiast forums, Hideriyama stones are described as relatively soft compared to other mines in the Kyoto region, with a fine-grained texture in the roughly 8000-10 000 grit range, making them ideal for the final stage of sharpening, aiming for a polished, but still "biting" edge.

These stones are often called "Iromono" (coloured) stones, as they have a variety of shades from yellowish to reddish or greyish, and their softness makes it easy to form sharpening suspensions, speeding up the process and ensuring smooth work on hard steel, such as the Japanese hagane knives. Hideriyama stones are easy to use and do not require soaking in water, but only light wetting ("splash and go"), like the vast majority of Japanese sharpening stones, which makes them attractive to both beginners and experienced sharpeners. Like many other traditional Japanese mines, Hideriyama is likely to have closed down or its resources are severely depleted, making these stones rare and highly prized by collectors and professionals alike, with prices in specialist shops reflecting the limited supply. Hideriyama stones are particularly suitable for 'kasumi' finishing and fine polishing, with a hardness rating of approximately 2.9 out of 5, which confirms their softer nature compared to the harder Nakayama or Aoto stones.

Ikeno-uchi (池ノ内)

The Ikeno-uchi mine near Ohira was mined until the late 19th century. Its stones, often Shiro type, soft and sophisticated. Toishi Den Ikeno-uchi stones are said to "soothe the blade like lake water". They are used in kitchen knives to Kasumi finishes. Shei Japanese sharpening stones are fine-grained, similar in hardness and texture to Nakayama stones, and are suitable for the final stage of sharpening, especially for Japanese knives, razors or other precision tools, to achieve a polished, mirror-like blade surface. Their colour can vary from greyish to reddish or yellowish and their texture allows efficient work on hard steels such as Japanese carbon steel knives. Like many traditional Japanese mines, Ikeno-uchi is probably now closed, and its stones have become rare and precious, prized among sharpening professionals and collectors for their rarity and quality. The mine is closed and its stones are rare.

Inokura (猪倉)

The Inokura mine, located in the Kameoka region, was known for its extremely coarse stones, which were mined until the early 20th century. Its stones, often Karasu type, dark and hard, suitable for initial sharpening. Masters call them "strong as a mountain stone" (『山の石』). Inokura stones are used in tools and katana swords to remove defects. The mine is closed and its stones are moderately rare.

Izariyama (イザリ山)

The Izariyama mine, located in the western part of Kyoto, was active until the end of the 19th century. Its stones, often Asagi type, greenish and fine-grained, suitable for or just before final polishing. Toishi Kō Izariyama stones are said to "give life to the blade". They are used in razors and knives to achieve a mirror-like surface. The mine is closed and its stones are rare.

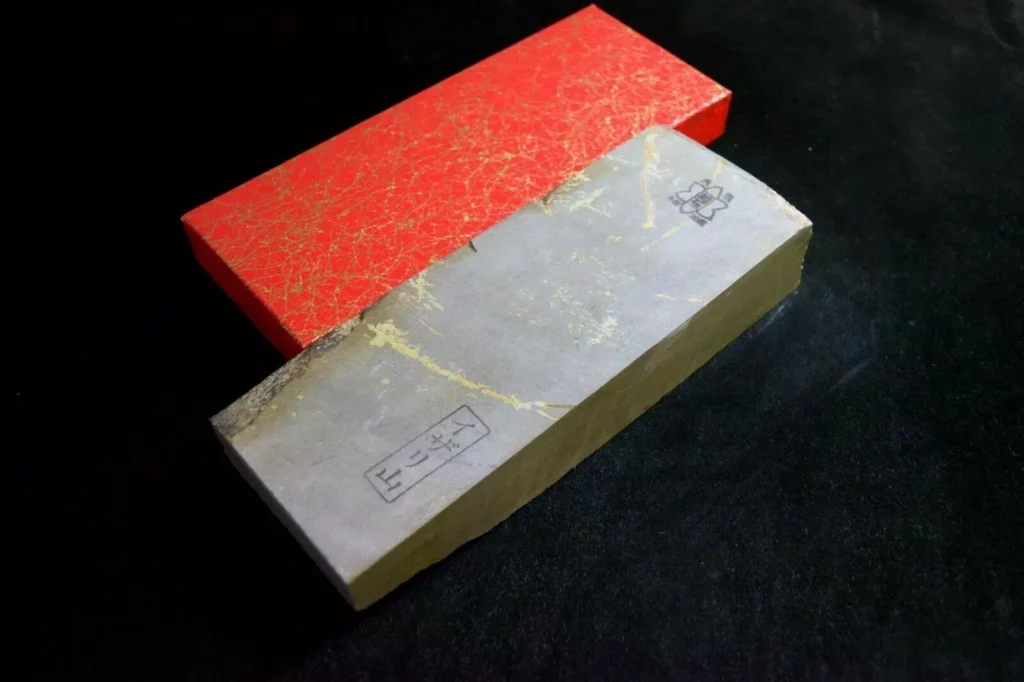

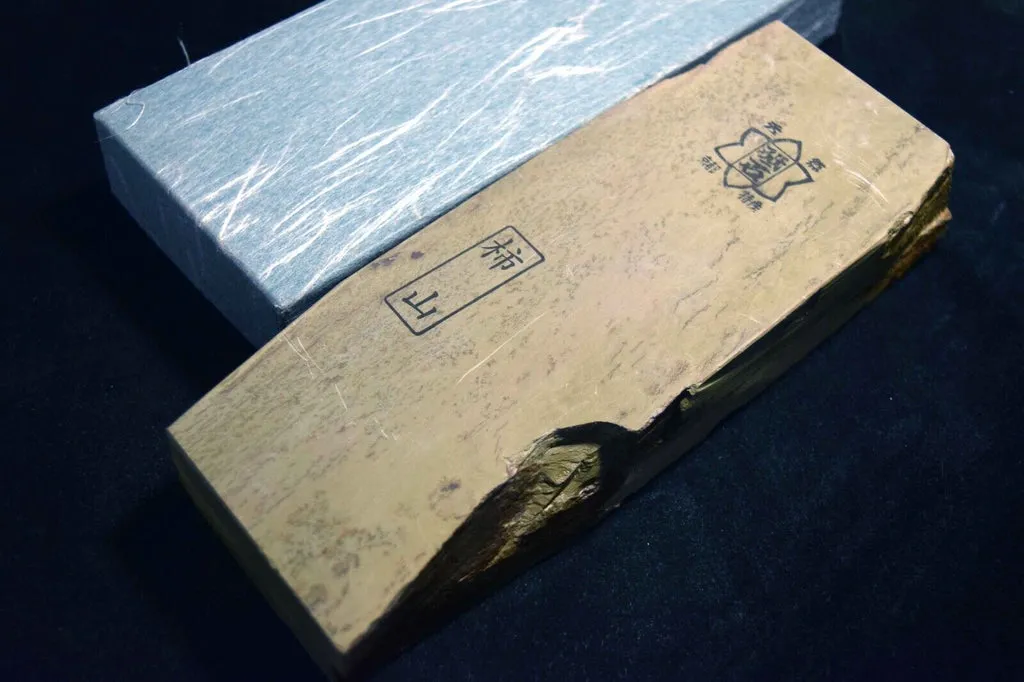

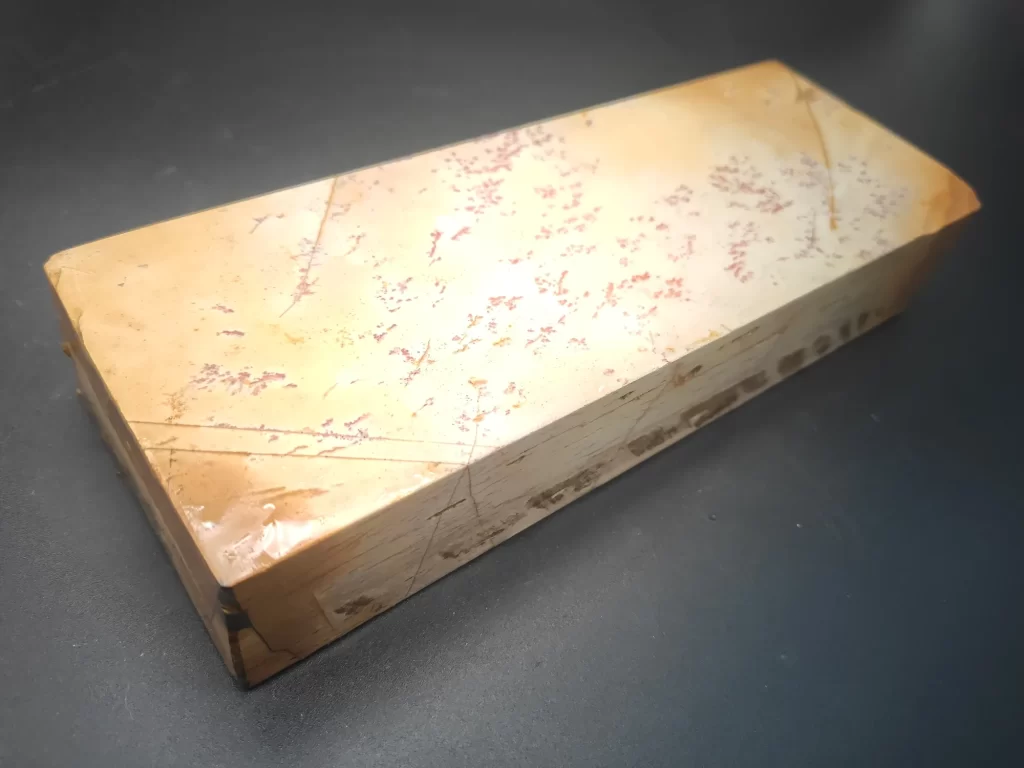

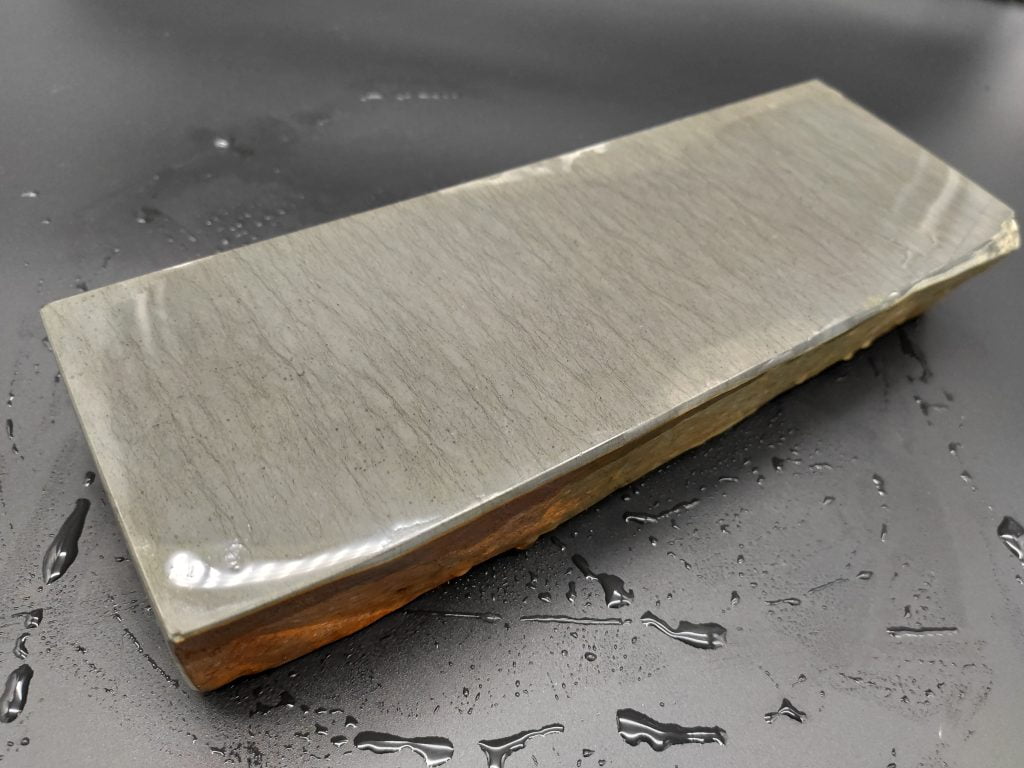

Kakiyama (柿山)

The Kakiyama mine, named after the persimmon-coloured stones, was mined until the early 20th century. Its stones, often Another one type, yellowish and fine-grained, suitable for final polishing and preparation. They are described by craftsmen as "warm like autumn fruit" (『秋の果実』). Kakiyama stones are used for razors and knives to achieve a mirror effect. The mine is closed and its stones are highly prized.

Maruoyama (丸尾山)

The Maruoyama mine, located near Ohira, is still active today. Its stones range from suita to soft stones suitable for polishing. Toishi Hon Maruoyama stones are said to "give the blade peace of mind". They are used in kitchen knives to Kasumi finish and maximum sharpness.

Mizukihara (水木原)

The Mizukihara mine, named for its watery terrain, was mined until the early 20th century. Its stones, often Asagi type, greenish and fine-grained, suitable for final polishing. Masters call them "fresh as river water" (『川の水』). Mizukihara stones are used for razors and knives to achieve a semi-mirror surface. The mine is closed and its stones are highly prized, especially the Mizukihara Uchigumori, which gives an ideal Kasumi finish and is harder than Ohira.

Momijiyama (紅葉山)

The Momijiyama mine, named after the colour of its autumn leaves, was active until the end of the 19th century. Its stones, often Another one type, yellowish and fine-grained, suitable for final polishing. Toishi Den Momijiyama's stones are said to "glow like maple leaves". They are used for razors and knives to achieve a mirror effect. The mine is closed and its stones are rare.

Kaedeyama (楓山)

The Kaedeyama mine, located in the western part of Kyoto, was mined until the early 20th century. Its stones, often Asagi type, greenish and fine-grained, suitable for final polishing. They are described by craftsmen as "soft as maple branches" (『楓の枝』). Kaedeyama stones are used for razors and knives to achieve a mirror-like surface. The mine is closed and its stones are highly prized.

Kouzaki/Kōzaki (Tanba, 神前)

The Kouzaki mine in the Tanba region was active until the end of the 19th century. Its stones, often dark and hard, are suitable for intermediate sharpening. Toishi Kō Kouzaki stones are said to "give the blade its power". They are used in katana swords and tools to Kasumi finishes. Kouzaki, also known as Kōzaki, is a historic sharpening stone mine located in the Tanba region, near Kameoka City in Kyoto Prefecture, Japan, known for its high quality Aoto stones.

Valued by professional sharpeners and craftsmen, these stones are distinguished by their hardness, fine texture and their ability to produce extremely sharp, polished blades, which is why they are often used as finishing stones for knives, razors and other precision tools. Kouzaki stones, often blue-grey in colour with yellowish or reddish undertones, reflect the Japanese sharpening tradition, where natural stones are valued for their unique qualities as opposed to their synthetic analogues. Like many other traditional mines, Kouzaki is now closed or severely depleted, making these stones rare, precious and coveted by collectors and professionals. It is worth contacting specialist shops or consulting experts to purchase Kouzaki stones, as their rarity and quality make them exceptional in the world of the art of sharpening.

Ohira (大平)

The Ohira mine, one of the most famous western mines, was mined until the mid-20th century. Its stones, often Asagi type, greenish and fine-grained, suitable for finishing knives. Masters call them "calm as a plain" (『平野の如く』). Ohira stones are used in joinery tools and knives to achieve a matt surface. The mine is still in operation today and its stones are not badly valued, especially by Uchigumori and Suita for the finish of the kasimu.

Okunomon (奥ノ門)

The Okunomon mine, located further west, was mined until the end of the 19th century. Its stones, often Shiro type, soft and suitable for intermediate sharpening. Toishi Hon Okunomon stones are said to "give the blade its delicacy". They are used in kitchen knives to Kasumi finishes. The mine is closed and its stones are rare.

Ogurayama (小倉山)

The Ogurayama mine, near Ohira, was active until the early 20th century. Its stones, often Another one type, yellowish and fine-grained, suitable for final polishing. Masters describe them as "warm as the mountain sun" (『山の陽』). Ogurayama stones are used for razors and knives to achieve a mirror effect. The mine is closed and its stones are highly prized.

Omoteyama (表山)

The Omoteyama mine, located in the western part of Kyoto, was mined until the late 19th century. Its stones, often Asagi type, greenish and fine-grained, suitable for final polishing. Toishi Den Omoteyama's stones are said to "reflect the beauty of the sky". They are used for razors and knives to achieve a mirror-like surface. The mine is closed and its stones are rare.

Otaniyama (大谷山)

The Otaniyama mine in the Tanba region was active until the early 20th century. Its stones, often Karasu type, dark and hard, suitable for prefinishing or finishing. Masters call them "rock-solid" (『山の岩』). Otaniyama stones are used for katana swords and tools to Kasumi finishes. The mine is closed and its stones are rare.

Hondo Daigokujo are the highest quality sharpening stones among Otaniyama stones. Mount Otani is located approximately 10 kilometres north-west of the centre of Kameoka Town Hall and is the common name of many mountains. It is a grinding stone layer containing many abrasive particles and appears to have been quarried during the Showa era, as the black colour was considered a bad luck and was avoided in the Edo period.

The quality of the stones is good, but they are not widely known because they were not allowed to join the Kyoto Natural Stones Association, because the latter did not like the cheap, high-quality stones on the market. Then a businessman, who mainly imported and sold lubricants, rods, irons, etc., spotted this grinding stone and sold it door to door to hairdressers all over Japan, and gradually it spread.

This stone is a mixture of Hondo-mae and Shiki-tomae, which gives the best finish. It can be compared to the Nakayama finish. At the time it was sold for about the same price as a university graduate's starting salary, but because it is a black stone, not everyone thinks it is worth that much. As for this grinding stone, it is slightly soft, so it can be used for knife finishing.

As the name suggests, it is a universal grinding stone that can be used not only for knives, but also for finishing razors, small knives, scissors, files, chisels, etc. The appeal of Otaniyama is that the result is similar to that of the highest quality sharpening stones.

Otoyama (音羽山)

The Otoyama mine, named after the melodious stream, was mined until the end of the 19th century. Its stones, often Asagi type, greenish and fine-grained, suitable for final polishing. Toishi Kō Otoyama stones are said to "sing in their blades". They are used in razors and knives to achieve a mirror finish. The mine is closed and its stones are highly prized.

Ōuchi/Oh-uchi (大内)

The Ōuchi mine, located in the western part of Kyoto, was active until the early 20th century. Its stones are often soft and suitable for intermediate sharpening. The craftsmen describe them as "calm as a valley" (『谷の静けさ』). Ōuchi stones are used for kitchen knives to Kasumi finishes. The mine is closed and its stones are rare.

Shinden (新田)

The Shinden mine, near Ohira, was mined until the mid-20th century. Its stones, often Asagi type, greenish and fine-grained, suitable for final polishing. Toishi Hon Shinden stones are said to "revitalise the blade like a new field". They are used in razors and knives to achieve a mirror-like surface. The mine is closed and its stones are highly prized.

Umaji / Umajiyama (馬路山)

The Umaji mine, located in the western part of Kyoto, was active until the end of the 19th century. Its stones, often Another one type, yellowish and fine-grained, suitable for final polishing. Masters call them "warm as the sun on the road" (『道の陽』). Umaji stones are used for razors and knives to achieve a mirror effect. The mine is closed and its stones are rare.

Yaginoshima (八木ノ嶋 or 八木嶋 or 八木の嶋)

The Yaginoshima mine, located in the Tanba region, was mined until the early 20th century. Its stones, often Asagi type, dark and quite hard, suitable for finishing knives. Toishi Den Yaginoshima stones are said to "give strength to the blade". They are used in katana swords and tools to Kasumi finishes. The mine is closed and its stones are rare.

Tamurayama

Mount Tamura in the Wakasa region (Fukui Prefecture) is one of the most important natural sources of sharpening stones in Japan. These stones are valued for their fine grain and excellent sharpening properties, suitable for sharpening knives, planes, chisels and razors. They are most commonly available in Kiita or Asagi colours.

Tamurayama honing stones are often hard and dense, ideal for shaping a sharp edge. Stones with a 'Tomae' layer are particularly appreciated by professionals. The result of sharpening is the 'cloudy' lustre and long-lasting sharpness characteristic of natural stones. The mine is currently in use and its stones are well appreciated by the Japanese Hairdressers' and Beauty Professionals' Association as the perfect finishing touch for razors.

Wakasa (若狭)

The Wakasa (若狭) sharpening stone mine, located in Fukui Prefecture near Kyoto, Japan, is a well-known source of Japanese Natural Sharpening Stones (JNATS), renowned for its hard and fine-grained stones that are particularly suited for the final sharpening stage.

Wakasa sharpening stones are often described as Asagi or Tomae-type, with a blue-grey or yellowish colour and a homogeneous structure that produces an extremely sharp, polished edge, ideal for Japanese razors (kamisori), high-end kitchen knives and other tools. The hardness of these stones is generally rated at 4-5 out of 5 and their fineness corresponds to a grain size range of approximately 6000-8000, making them ideal for precision sharpening, especially for fine finishes such as the 'kasumi' effect on Japanese knives.

Wakasa stones are splash and go, requiring no soaking, and their hardness and smoothness make them suitable for beginners and experienced sharpeners alike, although they can be slower to sharpen due to their dense structure. Like many traditional Japanese mines, the Wakasa mine is severely depleted, making these stones rare and expensive, often sold through specialist shops where the price reflects their rarity and quality.

Japanese sources point out that Wakasa stones, especially those of the Tamurayama layer, are valued for their cleanliness and uniformity, and their use is associated with the traditional Japanese art of sharpening, which emphasises not only functionality but also aesthetics.

Yuge (弓削)

The Yuge mine, located in the western part of Kyoto, was active until the late 19th century. Its stones, often Asagi type, greenish and fine-grained, suitable for final polishing. They are described by craftsmen as "flexible as a bow" (『弓の如く』). Yuge stones are used for razors and knives to achieve a mirror-like surface. The mine is closed and its stones are highly prized.

Conclusion

Japanese natural sharpening stones are not only functional tools, but also a cultural treasure, reflecting the beauty of Japan's mountains and the wisdom of its craftsmen. From Nakayama to Yuge, each mine has its own unique history, aesthetics and purpose, allowing craftsmen to create the perfect blade. Although most of the mines have now closed, their stones remain coveted by collectors and professionals alike, and their value is only increasing. The use of these stones is a tribute to the traditions and gifts of nature that embody Japanese aesthetics and craftsmanship.